Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. You can do whatever you like with it. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head

August 9, 2013 § Leave a comment

Do you feel like some ridiculously awesome, eagle-eyed super mutant? Martin tells io9 his goal in creating massive images has always been to extend the limits of human perception – what he calls the image’s “transhuman aspect.” The point is to feel like a goddamn superhero:

It’s the idea of creating a view that literally extends our senses far beyond what we can sense on our own. This image shows you orders of magnitude more stuff than you can see when you are actually there. Even if you are on Tokyo Tower with binoculars or a telescope, this image shows you more than you can possibly take in, in person.

The founder of 360Cities.net, a website where photographers can upload 360-degree images of beautiful locations around the globe, Martin is no stranger to this medium. He’s even created an image that’s bigger than the one you see here, but this one, he says, is his favorite. look

ART: Inomati Aki

I made no attempt to contact any of the people who had been so important to me in the past. I had already let important connections unravel through inattention, and that carelessness has been a bane to me all my life

August 7, 2013 § Leave a comment

Debate is heating up in Tokyo about the advisability of hiking Japan’s consumption tax. Which should come first- economic growth or fiscal reconstruction? The prime minister must decide in a matter of weeks.

It’s after midnight and I’m sitting in a Roppongi bar discussing the subject with a knowledgeable Japanese bureaucrat.

“It’s essential to raise taxes,” he says, cradling a well-aged Islay malt. “If we don’t, investors will lose confidence and our bond market will collapse.”

“Aren’t you risking a serious recession?”

“A temporary blip, maybe. But the strengthening of public finances will be good for future growth.”

The year was 1997. read more

FILM: Longplayer

“Have you decorated?” “No, Madame, I have moved.”

August 6, 2013 § Leave a comment

This is cinema for the post-theatrical era. And people complained that the film was going to go straight to video. Well, we said: “Let’s make something that’s not for theaters.” It will have a theatrical release. But it’s going to have day-and-date. The whole motif of the derelict movie theaters was there right from the beginning.

Bret has this post-Empire idea. He believes that American artists are now in their post-Empire period. Like the Brits were in the previous century. So we’re making art out of the remains of our empire. The junk that’s left over. And this idea of a film that was crowd-funded, cast online, with one actor from celebrity culture, one actor from adult-film culture, a writer and director who have gotten beaten up in the past—felt like a post-Empire thing. And then everything I was afraid of with Lindsay and James started to become a positive. I was afraid we wouldn’t be taken seriously and people would think it’s a joke. My son and my daughter didn’t want me to do it. This just shows you how conservative young kids are. Because they thought it would be embarrassing and a disaster.

The number-one fact of the new low-budget cinema is that it is no longer impossible to get your film financed, but it is impossible to get anybody to see it. Because there are 10,000 people doing the same thing you’re doing, right now. And which one of those 10,000 films is anybody going to see? Fifteen thousand films get submitted to Sundance, 100 or so get shown, eight get picked up, and two make money. Those are the economics. But Bret and I have some cachet. We were in with four different sub-groups of interested people: people who are interested in me, people who are interested in Bret, people who are interested in Lindsay, and people who are interested in James. Lindsay has four million [Twitter] followers, and James has half a million. Bret has 250,000.

How do you see your career in light of your experience on this film?

I went to the casino, I put it all on red, and it came up red. We got lucky with this one. We got lucky with James, we got lucky with Lindsay. We got lucky with the noise factor. When you’re pitching a movie, that’s the question they ask: is it going to make noise? Are you going to hear this above the din of the avalanche of film productions? And if the idea has noise, then they are interested in it. And this idea had noise. Some of it by design, some of it by luck. That’s why I went to Bret, because if it was the two of us together it was going to make noise.

Obviously, Lindsay didn’t have a problem with James Deen.

Oh yes, she did. read more

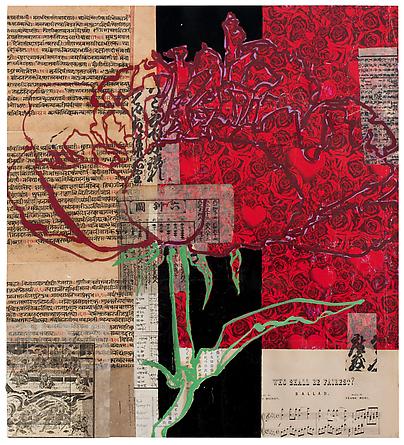

ART: Robert Kushner

I have found out what economics is; it is the science of confusing stocks with flows

August 5, 2013 § Leave a comment

Brendan O’Connor is a security researcher. How easy would it be, he recently wondered, to monitor the movement of everyone on the street – not by a government intelligence agency, but by a private citizen with a few hundred dollars to spare?

Mr. O’Connor, 27, bought some plastic boxes and stuffed them with a $25, credit-card size Raspberry Pi Model A computer and a few over-the-counter sensors, including Wi-Fi adapters. He connected each of those boxes to a command and control system, and he built a data visualization system to monitor what the sensors picked up: all the wireless traffic emitted by every nearby wireless device, including smartphones.

Each box cost $57. He produced 10 of them, and then he turned them on – to spy on himself. He could pick up the Web sites he browsed when he connected to a public Wi-Fi – say at a cafe – and he scooped up the unique identifier connected to his phone and iPad. Gobs of information traveled over the Internet in the clear, meaning they were entirely unencrypted and simple to scoop up.

Even when he didn’t connect to a Wi-Fi network, his sensors could track his location through Wi-Fi “pings.” His iPhone pinged the iMessage server to check for new messages. When he logged on to an unsecured Wi-Fi, it revealed what operating system he was using on what kind of device, and whether he was using Dropbox or went on a dating site or browsed for shoes on an e-commerce site. One site might leak his e-mail address, another his photo.

“Actually it’s not hard,” he concluded. “It’s terrifyingly easy.”

Also creepy – which is why he called his contraption “creepyDOL.”

“It could be used for anything depending on how creepy you want to be,” he said. read more

ART: Ernst Wille

In 2010, for the first time in US history, the number of poor living in the suburbs exceeded those living in the cities

August 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

The modern attitude toward forgery seems then to involve a number of features, some of which only gradually developed late in the Renaissance or after. One is the belief that works of art of all periods have a certain intrinsic value and that their historical and stylistic character should be respected, including, to some degree at least, the inevitable changes wrought by time. This belief was not held by early modern collectors of ancient art, or, for that matter, by church authorities and others who commissioned new versions of the images of the Madonna attributed to Saint Luke. Another requirement is the existence of an active art market. Finally, there has to be some widely accepted mechanism for determining the authenticity of the objects bought and sold in that market.

The art market as such began to develop in the later sixteenth century, and has continued to expand ever since. Like many other scholars, Lenain singles out the seventeenth-century Roman physician and writer on art Giulio Mancini as a pioneer in the discussion of what was later called connoisseurship, concentrating on his treatment of the expertise required to distinguish between an original and a copy. Mancini recommended that collectors should try to acquire at least a basic level of such expertise, and suggested ways in which they could do so. It is important to bear in mind, however, that this expertise did not cover the ability to identify the authors of works of art of the past. Mancini did not dissent from the conventional belief that the final authorities in all such matters were practicing artists, and this remained the general view until the nineteenth century.

Such artists certainly possessed a degree of knowledge beyond that of almost every amateur, simply because they knew how to paint or carve, and had studied by copying the works of others. But it is evident from inventories and sale catalogs that even in the late eighteenth century attributions were often highly optimistic and unreliable. This is not surprising, given the still primitive knowledge of art history and the absence of photographs and other reproductions. It is usually impossible to say whether copies or pastiches from that period, which survive in great numbers, were made as forgeries or in good faith.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, there is no doubt about the existence of art forgery as a significant phenomenon. It coincided with the emergence of professional connoisseurs, who claimed a particular expertise in identifying the authors of works of art, and, inevitably, in the detection of forgeries. Few of the connoisseurs had been trained as artists, and none of them continued to practice as such. But they had broad firsthand knowledge of works of art, usually a familiarity with the developing study of the history of art, and were normally associated in some way with the increasing numbers of art museums.

As both Lenain and Keats stress, the task of the forger is not just to create a work of art in the style of another artist, but to do so in such a way that it meets the expectations of a connoisseur and gives him (or very rarely her) the frisson of having made a discovery. Thus Hans van Meegeren, the celebrated Dutch forger of Vermeer, chose to imitate not Vermeer’s mature works, of which a considerable number existed, but his rather different and very rare early religious paintings, of which the first had been identified by an expert named Abraham Bredius. He accordingly submitted his first major forgery to Bredius, in the confident belief that it would fit with his preconceptions of what an early Vermeer ought to look like. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: jo(e)

there are some authors who employ their talent in the delicate description of varying states of the soul, character traits etc. I shall not be counted among these. All that accumulation of realistic detail, with clearly differentiated characters hogging the limelight, has always seemed pure bullshit to me

August 1, 2013 § Leave a comment

In The London Spy (1703), Ned Ward described coffee as a ‘Mahometan gruel’, whilst in 1665 an anonymous description of The Character of a Coffee-House insisted on its title-page that ‘When Coffee once was vended here, / The Alc’ron shortly did appear’. Another anonymous writer launched A Broadside against Coffee: or, The Marriage of the Turk in 1672.

Recognising the foreign roots of this increasingly popular drink, English writers worried that the potency of the fashionable beverage might cause imbibers to ‘turn Turk’, or become muslims. This was a surprisingly common fear in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as Matar has shown, fuelled by stories of Englishmen prospering as muslims. Stories of conversion and compulsion persisted, despite the fact that Islam was much more tolerant of other religions than were the Christian churches and that the Qur’an accords a special place to the two other religions of the book: Christianity and Judaism.

Coffee might affect body and soul together: changing the complexion to a swarthier hue and, as ‘an ugly Turkish enchantress’, putting the drinker under the ‘spell’ of another religion (The city-wifes petition against coffee (1700)). In 1663, the writer of a broadsheet description of A Cup of Coffee: or Coffee in its Colours complained:

For Men and Christians to turn Turks, and think

T’excuse the Crime because ’tis in their drink,

Is more then Magick, and does plainly tell

Coffee’s extraction has its heats from hell.

The complaint at coffee and its apostasizing effects seems to have had numerous causes: a patriotic attempt to keep native industries alive by persuading Englishmen to keep drinking the more traditional ale and beer; a fear of the very real military might of the Ottoman Empire; and a way to explain the physical effects of coffee (argued by some to be an aphrodisiac, whilst others complained it turned English husbands into ‘Eunuchs’). read more

STILL: Christian Roger

He spoke of latent causes, sterile gauzes and the bedside morale

July 31, 2013 § Leave a comment

Stoker opened by telling Whitman that he could burn the letter, but hoped that he would resist. “I don’t think there is a man living, even you who are above the prejudices of the class of small-minded men, who wouldn’t like to get a letter from a younger man, a stranger, across the world—a man living in an atmosphere prejudiced to the truths you sing and your manner of singing them.” He greatly valued Whitman’s candor, regarding him as different from other men, and hoped that they could be friends. “If I were before your face I would like to shake hands with you, for I feel that I would like you. I would like to call you Comrade and to talk to you as men who are not poets do not often talk.” Stoker then declared Whitman to be a “true man,” confessing that he yearned to be one himself, “and so I would be towards you as a brother and as a pupil to his master.”

Having made his admiration known, Stoker described his life: He was twenty-four years old, named after his father; his friends called him Bram, and he earned a small salary working as a clerk for the government. Next came his person and demeanor:

I am six feet two inches high and twelve stone weight naked and used to be forty-one or forty-two inches round the chest. I am ugly but strong and determined and have a large bump over my eyebrows. I have a heavy jaw and a big mouth and thick lips—sensitive nostrils—a snubnose and straight hair. I am equal in temper and cool in disposition and have a large amount of self control and am naturally secretive to the world. I take a delight in letting people I don’t like— people of mean or cruel or sneaking or cowardly disposition—see the worst side of me.

Stoker included his physical description, because he surmised from Whitman’s works and his photograph that he would be interested to know the “personal appearance of your correspondents.” Wrote Stoker: “You are I know a keen physiognomist.”

Stoker attempted to convey what Whitman’s poetry meant to him. “I have to thank you for many happy hours, for I have read your poems with my door locked late at night, and I have read them on the seashore where I could look all round me and see no more sign of human life than the ships out at sea: and here I often found myself waking up from a reverie with the book lying open before me.” Whitman’s verse had been life-changing for a self- confessed conservative from a conservative country. “But be assured of this, Walt Whitman—that a man . . . who has always heard your name cried down by the great mass of people who mention it, here felt his heart leap towards you across the Atlantic and his soul swelling at the words or rather the thoughts.”

Stoker closed by acknowledging his frankness. “I have been more candid with you—have said more about myself to you than I have ever said to any one before. You will not be angry with me if you have read so far. You will not laugh at me for writing this to you. It was with no small effort that I began to write and I feel reluctant to stop, but I must not tire you any more.” read more

PHOTOGRAPH: [unattributed]

One of Drew’s feet flew up and touched my calf, and we were free and in hell

July 29, 2013 § Leave a comment

Most government statistics are mapped according to official geographical units such as wards or lower super output areas. Whilst such units are essential for data analysis and making decisions about, for example, government spending, they are hard for many people to relate to and they don’t particularly stand out on a map. This is why we tried a new method back in July to show life expectancy statistics in a fresh light by mapping them on to London Tube stations. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Yamauchi Yu