One can approve vulgarity in theory as a comment on vulgarity, but in practice all vulgarity is inseparable

May 30, 2013 § 2 Comments

One of the great proponents of moving walkways was Jesse Wilford Reno (1861-1947). In 1891 he applied for the first US patent for what we would recognize as a relatively modern moving walkway (granted 1892). However this early concept had to wait while Reno concerned himself with a slightly different idea.

Reno’s first machine was installed in 1896 as a mere pleasure ride at Coney Island, New York, at the Old Iron Pier. He termed it his ‘inclined elevator’ and it was inclined at 20 degrees and had a rise of only seven feet and a speed of about 75 ft/minute. In fact it was provided to act as a means of demonstrating its capabilities to potential customers, such as the trustees of the Brooklyn Bridge and subway and elevated railway operators. This ploy seems to have worked as machines were deployed at each end of the bridge (I think in 1896). Strange to say that it was only after this that the idea of constructing a horizontal machine was suggested, initially as a means of crossing the bridge, but this was not pursued.

So far as I have been able to establish, his 7 ft demonstrator only ran for two weeks but had the peculiar property that passengers were required to sit on it, as though it were some kind of inverted ski lift. It was therefore a passenger conveyor, but not a walkway. I am yet to discover more about this, especially as it is reputed to have gone to Brooklyn Bridge to impress the managers there (I believe for two months but struggle to confirm this). There is an image, produced below, of a sitting-down type conveyor at Coney Island, probably made by Reno, but it is obviously much more than 7 ft high and has a permanent look about it. Perhaps it was installed soon after as a result of a successful trial. It is apparent that this design departed very considerably from his 1892 patent and does not seem to have been repeated. Though Coney island is frequently cited as ‘the first escalator’, the evidence tends to suggest it was very different in conception and not part of the mainstream development of passenger conveyors. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Richard Perkins

the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America’s profiles of five types of book thieves: the kleptomaniac who cannot keep himself from stealing; the thief who steals for profit; the thief who steals in anger; the casual thief; and the thief who steals for his own personal use

May 28, 2013 § Leave a comment

Guy Abeille, age 62, a former senior Budget Ministry official and “the inventor of the concept, endlessly repeated by all governments whether of the right or the left, that the public deficit should not exceed 3% of the national wealth,” told the newspaper –

We came up with the 3% figure in less than an hour. It was a back of an envelope calculation, without any theoretical reflection. Mitterrand needed an easy rule that he could deploy in his discussions with ministers who kept coming into his office to demand money. […] We needed something simple. 3%? It was a good number that had stood the test of time, somewhat reminiscent of the Trinity. read more

FILM: Yolanda Domínguez

Diese excessive technicality of ancient law zeigt Jurisprudenz as feather of the same bird, als d. religiösen Formalitäten z. B. Auguris etc. od. d.. Hokus Pokus des medicine man der savages

May 27, 2013 § Leave a comment

I know virtually nothing about the practical side of film-making. The practical side of any art is the only side really worth going on about and the only side that can be endlessly articulate, but I personally take about one snap shot every twenty years, so the technical and creative sides of photography, which can be unbelievably complicated both physically and mentally, are almost unknown to me, and I must speak as one of the idle audience, who simply looks at films.

From this point of view I find the films of Stan Brakhage are not only of the highest interest in the contemplation but of the first importance in the current history of this form of art, because they have a dramatic vitality of eyesight which is something unique and very much his own. That is to say, that the things which he and his camera see may be dramatically interesting or they may not, but the act of seeing it, with Brakhage, is intensely dramatic, and it is this dramatic continuity of seeing which commands or determines the sequences and associations of the things seen, and which is, for me, the heart and meaning of his films, especially of Prelude. This seeing is dramatic, not simply theatrical or pictorial. Much fancy photography in Hollywood, and plenty of decent art photography, like that of say Eisenstein, is theatrical: it is the inner and passionate and raw act of seeing, converted into a handsome exterior gesture. The most refined trickery of cutting, of panning, of lighting etc. results normally in a sort of visual rhetoric — to which I have no objections except that it is, to use a distinction of Gertrude Stein’s, more lively than alive. As it can be seen from Colorado Legend — Brakhage can command this rhetoric beautifully, in a rather advanced and thoroughly enjoyable commercial film, but he has a much greater and distinguished gift. This is for the direct dramatic sight of things, which seem, under the pressure and provocation of his stare, to force themselves on the camera in their own order and deportment as much as they seem to be selected or guided by the camera. The result, or rather the action, is a sort of hostile or erotic struggle between eye and object — as against the eye and object both posing or dancing elegantly for your disengaged pleasure. read more

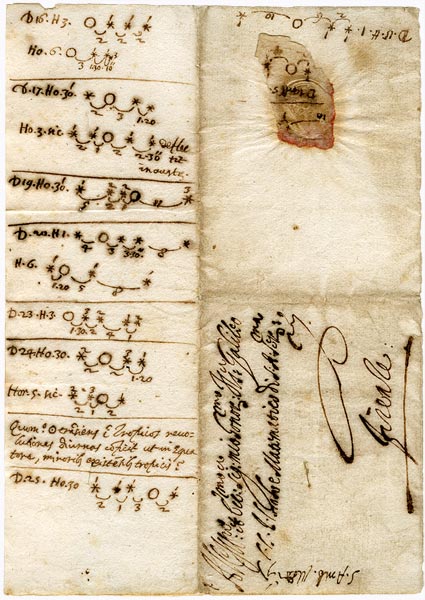

NOTES: Galileo Galilei

As you see, in most of his paintings of Alice he has been forced to disguise her as arable land

May 24, 2013 § Leave a comment

In the US and Canada, there were at end 2012 still over 6400 commercial analog screens, or about 15% of the nearly 43,000 total. My home town, Madison, Wisconsin, has a surprising number of these anachronisms. One multiplex retains at least two first-run 35mm screens. Five second-run screens at our Market Square multiplex have no digital equipment. That venue ran excellent 2D prints of Life of Pi (held over for seven weeks) and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. It’s currently screening many recent releases, including the incessantly and mysteriously popular Argo. In addition, our campus has several active 35mm venues (Cinematheque, Chazen Museum, Marquee). Our department shows a fair amount of 35mm for our courses as well; the last screening I dropped in on was The Quiet Man in the very nice UCLA restoration.

Unquestionably, however, 35mm is doomed as a commercial format. Formerly, a tentpole release might have required 3000-5000 film prints; now a few hundred are shipped. Our Market Square house sometimes gets prints bearing single-digit ID numbers. Jack Foley of Focus Features estimates that only about 5 % of the copies of a wide US release will be in 35mm. A narrower release might go somewhat higher, since art houses have been slower to transition to digital. Focus Features’ The Place Beyond the Pines was released on 1442 screens, only 105 (7%) of which employed 35mm.

In light of the rapid takeup of digital projection, Foley expects that most studios will stop supplying 35mm copies by the end of this year. David Hancock has suggested that by the end of 2015, there won’t be any new theatrical releases on 35mm.

Correspondingly, projectionists are vanishing. In Madison, Hal Theisen, my guide to digital operation in Chapter 4 of Pandora, has been dismissed. The films in that theatre are now set up by an assistant manager. Hal was the last full-time projectionist in town.

The wholesale conversion was initiated by the studios under the aegis of their Digital Cinema Initiatives corporation (DCI). The plan was helped along, after some negotiation, by the National Association of Theatre Owners. Smaller theatre chains and independent owners had to go along or risk closing down eventually. The Majors pursued the changeover aggressively, combining a stick—go digital or die!—with several carrots: lower shipping costs, higher ticket prices for 3D shows, no need for expensive unionized projectionists, and the prospect of “alternative content.”

The conversion to DCI standards was costly, running up to $100,000 per screen. Many exhibitors took advantage of the Virtual Print Fee, a subsidy from the distributors that paid into a third-party account every time the venue booked a film from the Majors. There were strings attached to the VPF. The deals are still protected by nondisclosure agreements, but terms have included demands that exhibitors remove all 35mm machines from the venue, show a certain number of the Majors’ films, equip some houses for 3D, and/or sign up for Network Operations Centers that would monitor the shows. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Chris Phillips

Too, there is no theme

May 23, 2013 § Leave a comment

Today I have been mostly investigating the rules of irony. It turns out they are set in stone.

I had a slightly puzzling start with two spurious defects before I’d even got out of a siding. I say “spurious” but I’m not entirely sure. The trains have been acting funny lately with all sorts of things happening that shouldn’t. The current favourite game in the messroom is chucking around theories on what went wrong with particular trains and how to fix them. As I was alone in the siding I didn’t have anyone to bounce ideas off but I did spend some time trying to work out how the train could have been defective. For the first defect I couldn’t come up with anything mechanical. When you find yourself seriously considering the actions of a passing badger in the middle of the night you realise you might need a bit more coffee. So I had some and continued to think about badgers. read more

FILM: thisnoisecountry

I see he’s just typed out, ‘The cat’s in the bag, and the bag’s in the river.’ It took my breath away, right from his brain to my brain

May 22, 2013 § Leave a comment

To insist that the Spanish crisis is the consequence of venality, stupidity, greed, moral obtuseness and/or political short-sightedness, which has become the preferred explanation of moralizers across Europe begs the question as to why these unflattering qualities only manifested themselves after Spain joined the euro. Were the Spanish people notably more virtuous in the 20th century than in the 21st? It also begs the question as to why vice suddenly trumped virtue in every one of the countries that entered the euro with a history of relatively higher inflation, while those eastern European countries with a history of relatively higher inflation that did not join the euro managed to remain virtuous.

The European crisis, in other words, had almost nothing to do with thrifty Germans and spendthrift Spaniards. It had to do with policies aimed at boosting German employment, the secondary impact of which was to force up German national savings rates excessively. These excess savings had to be absorbed within Europe, and the subsequent imbalances were so large (because German’s savings imbalance was so large) that they led almost inevitably to the circumstances in which we are today.

For this reason the European crisis cannot be resolved except by forcing down the German savings rate. And not only must German savings rates drop, they must drop substantially, enough to give Germany a large current account deficit. This is the only way the rest of Europe can unwind the imbalances forced upon the region in a way that is least damaging to Europe as a whole. Only in this way can countries like Spain stay within the euro while bringing down unemployment.

But lower German savings don’t mean that German families should become less thrifty, only that the average German household should be allowed to retain a much larger share of what Germany produces. If Berlin were to cut consumption taxes, or cut income taxes for the lower and middle classes, or force up wages, total German consumption would rise relative to GDP and so national savings would fall – without requiring any change in the prudent behavior of German households.

To ask Spanish households to be more “German” by saving more is not only impractical in an economy with 25 percent unemployment (it is hard for unemployed workers to increase their savings), it is counterproductive. Lower Spanish consumption can only cause even higher Spanish unemployment, until eventually Spain will be forced to abandon the euro and so regain control of its ability to absorb or reject German imbalances. This abandonment of the euro will be driven by the political process, as those in the leadership (of both main parties) who refuse to countenance talk of leaving the euro lose voters to more radical parties until they, too, come around. read more

FILM: Tedd Tramaloni

“You don’t have to watch anything close anymore,” he tells Dr. Onarga, at one appointment, “’cause it’ll always be repeated.”

May 21, 2013 § Leave a comment

I have been known to buy them in moments of weakness, but I don’t really approve of joke cookbooks. I own dozens of cookbooks with barely usable recipes, but I make a distinction between books that are intentionally bad and those that have merely aged poorly. Cooking for Orgies and Other Large Parties: How to Cook and Serve Fabulous Six-Course Gourmet Dinners for Ten to Thirty People in One Hour for $1.00 per Person has always been a crowd pleaser, though, and I feel some genuine affection for it.

The authors, Jack S. Margolis and Daud Alani, claim to be “Hollywood Bachelors” with no first-hand knowledge of orgies. Their “friend,” Ernie Lundquist, “has an orgy… every Wednesday night at 9:00 p.m.,” and has taught them everything they know. Perhaps because of their lack of experience, or perhaps, as I suspect, because they are mostly excited about their cooking method (see below), Margolis and Daud don’t devote much of the book to talk of orgies. There are naughty line drawings throughout, and there is a perfunctory “Special Consideration” section at the beginning, complete with a suggested time-table (“9:30-12:00: Free Play”), but that’s about it. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Kawaguchi Haruhiko

sext me with spelling errors and bad grammar so i know it’s real

May 20, 2013 § 1 Comment

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an emerging medium in possession of a large audience must be in want of a Pride and Prejudice adaptation.

Enter The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, a retelling of Jane Austen’s most famous novel as a modern-day Lizzie’s serialized video blog, In this version, Lizzie is “a 24-year-old grad student with a mountain of student loans, living at home and preparing for a career,” but despite her unglamorous circumstances, she still bewitched plenty of viewers. The series posted its last episode this March and went on to complete a Kickstarter campaign for a DVD that raised 800% of its initial goal and made it the site’s fourth-most funded video/ film project. Lizzie and Darcy are, apparently, just as compelling on YouTube as they are on page and screen.

Jane Austen’s internet success isn’t so surprising. She is, after all, one of those few authors who live on as both a pop-cultural phenomenon and a dissertation topic. In fact, given her talent for snarky dialogue, Austen and the internet seem like a perfect match. For what do we use social media, after all, but to make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn?

The series is well-acted and adapted with skill and sensitivity, but what turned it in my mind from a quality procrastination device to an object of critical attention was an analysis of Austen’s popularity I read while researching my obsession: the similarity between the 1790s panic over proliferating print-culture and our own internet anxieties. In The Work of Writing, Clifford Siskin argues that the reason Austen enjoyed lasting success while many of her female contemporaries were forgotten was because she and her novels helped to make the technology of writing feel comfortable and safe. Contemporary reviews of Emma praised it as “inoffensive” and “a harmless amusement.” Siskin ties the safety of Austen’s novels to the way her stylistic and publication choices assuaged turn-of-the-19th century concerns about the power of writing. Her ironic treatment of sentimental situations contrasted favorably with “sentimental novels” that critics feared would unduly influence the feelings and actions of their readers. Her decision to publish her novels as stand-alone volumes rather than serially in periodicals played into the creation of a hierarchy of publication modes (books over magazines) that helped to conquer writing by dividing it.

Siskin focuses his analysis on Northanger Abbey, the Austen novel that takes the novel itself as one of its themes. The novel’s heroine is rather fixated on gothic romances, and occasionally interprets real life through the prism of her reading material, to embarrassing and comedic effect, but without disastrous consequences. Siskin writes of Northanger:

“The discomforting question is whether we become what we read. Austen’s answer—an answer that I would argue signals a change in the status of writing from a worrisome new technology to a more trusted tool—is “Yes and no, but don’t worry.”

Procrastinating to The Lizzie Bennett Diaries while researching Romantic-era print culture, I realized that what Austen did for the novel, LBD creators Hank Green and Bernie Su do for the vlog, and digital media generally. They take a story telling medium that is new and strange and potentially threatening, and they make it comfortable. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Carmen Gonzalez