Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains

December 16, 2013 § Leave a comment

Do you remember the fog, eh? It seems like over a century ago, but it was only yesterday. It was a different age. A simpler, foggier age

December 12, 2013 § Leave a comment

Yes, it’s a Markov chain generator, seeded with the King James Bible and the complete works of H. P. Lovecraft. Sample output:

krina:markov charlie$ ./lovebible.pl 2> /dev/null 99820 lines, 821134 words read from king_james_bible.txt 16536 lines, 775603 words read from lovecraft_complete.txt About to spew ...--- the backwoods folk -had glimpsed the battered mantel, rickety furniture, and ragged draperies. It spread over it a robber, a shedder of blood, when I listened with mad intentness. At last you know! At last to come to see me. Now Absalom. the absence of any real link with that of 598 Angell Street was as the old castle by the shallow crystal stream I saw unwonted ripples tipped with yellow light, as if those depths of their rhythm. The training saved them. the bed, and make thee borders of gold with studs of silver. 1:12 While the case histories, to expect. As mental atmosphere. His eyes were pits of a hundred and fifty shekels, 30:24 And he laughed mockingly at the village summoning. the commandment of the room; then this.

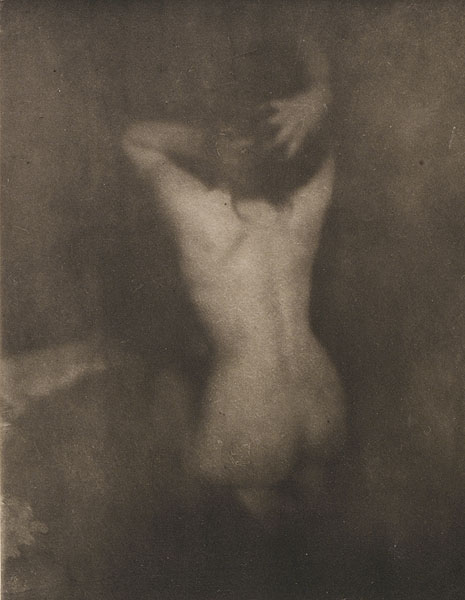

PHOTOGRAPH: Edward Steichen

It’s OK to sleep, you’ll still be miserable in the morning

December 10, 2013 § Leave a comment

During the past decade or two, there’s been a growing body of work arguing for a special connection between endogenous brain rhythms and timing patterns in speech. Thus Anne-Lise Giraud & David Poeppel, “Cortical oscillations and speech processing: emerging computational principles and operations”, Nature Neuroscience 2012:

Neuronal oscillations are ubiquitous in the brain and may contribute to cognition in several ways: for example, by segregating information and organizing spike timing. Recent data show that delta, theta and gamma oscillations are specifically engaged by the multi-timescale, quasi-rhythmic properties of speech and can track its dynamics. We argue that they are foundational in speech and language processing, ‘packaging’ incoming information into units of the appropriate temporal granularity. Such stimulus-brain alignment arguably results from auditory and motor tuning throughout the evolution of speech and language and constitutes a natural model system allowing auditory research to make a unique contribution to the issue of how neural oscillatory activity affects human cognition…

A possible weakness of Luo and Poeppel 2007 (a fascinating and deservedly influential study) was that the same phase analysis that they found to identify the brain responses to different sentences also worked in exactly the same way when applied to the amplitude envelope of the original audio. This suggests that simple modulation of auditory-cortex response by input signal amplitude might be the main mechanism, rather than any more elaborate process of phase-locking of endogenous brain rhythms. read more

MAP: Environmental Agency

With legs almost like you

December 9, 2013 § Leave a comment

“It was while looking at Google’s scan of the Dewey Decimal Classification system that I saw my first one—the hand of the scanner operator completely obscuring the book’s table of contents,” writes the artist Benjamin Shaykin. What he saw disturbed him: it was a brown hand resting on a page of a beautiful old book, its index finger wrapped in a hot-pink condom-like covering. In the page’s lower corner, a watermark bore the words “Digitized by Google.”

There are several collections of Google hands around the Web, each one as creepy as the one Shaykin saw. A small but thriving subculture is documenting Google Books’ scanning process, in the form of Tumblrs, printed books, photographs, online videos, and gallery-based installations. Something new is happening here that brings together widespread nostalgia for paperbound books with our concerns about mass digitization. Scavengers obsessively comb through page after page of Google Books, hoping to stumble upon some glitch that hasn’t yet been unearthed. This phenomenon is most thoroughly documented on a Tumblr called The Art of Google Books, which collects two types of images: analog stains that are emblems of a paper book’s history and digital glitches that result from the scanning. On the site, the analog images show scads of marginalia written in antique script, library “date due” stamps from the mid-century, tobacco stains, wormholes, dust motes, and ghosts of flowers pressed between pages. On the digital side are pages photographed while being turned, resulting in radical warping and distortion; the solarizing of woodcuts owing to low-resolution imaging; sonnets transformed by software bugs into pixelated psychedelic patterns; and the ubiquitous images of workers’ hands.

The obsession with digital errors in Google Books arises from the sense that these mistakes are permanent, on the record. Earlier this month, Judge Denny Chin ruled that Google’s scanning, en masse, of millions of books to make them searchable is legal. In the future, more and more people will consult Google’s scans. Because of the speed and volume with which Google is executing the project, the company can’t possibly identify and correct all of the disturbances in what is supposed to be a seamless interface. There’s little doubt that generations to come will be stuck with both these antique stains and workers’ hands. read more

ART: Tachibana Seiko

you juggle things cause you can’t lose sight of the wretched storyline

December 6, 2013 § Leave a comment

How on earth did apartheid endure so long, younger viewers may be wondering, considering everyone who was anyone seems to have been on Mandela’s side? read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Robin Juan

Three towns painted later in the same vein

December 5, 2013 § Leave a comment

So how was it possible that the British soldier was able to enact and organise the ‘live and let live’ philosophy with the ‘enemy’? Ashworth explains that this did not necessarily involve direct verbal communication between the opposing forces:

This understanding was tacit and covert; it was expressed in activity or non-activity rather than in verbal terms. The norm was supported by a system of sanctions. In the positive sense it constituted a system of mutual service, each side rewarded the other by refraining from offensive activity on the condition, of course, that this non-activity was reciprocated.

So an ‘understanding’ was reached, by careful study of action and reaction by the troops on both sides, about acceptable levels of violence. This was enforced by a negative sanction if the unwritten and non-verbalised ‘agreement’ was infringed as one British soldier recounted:

…the incident related occurred during an un-certain period during which the Germans appeared to be exceeding the existing level of offensiveness. ‘The Germans about this time also fired minenwerfers [Minenwerfer (‘mine launcher’) was a class of short range mortars used extensively during the First World War by the German Army. The weapons were intended to be used by engineers to clear obstacles including bunkers and barbed wire; that longer range artillery would not be able to accurately target.] into our poor draggled front line; this in-humanity could not be allowed and the rifle grenades that went over no-man’s-land in reply, for once almost carried out the staffs’ vicarious motto: give them three for every one. One glared hideously at the broken wood and clay flung up from our grenades and trench-mortar shells in the German trenches, finding for once that a little hate was possible.’ The arrival of the minenwerfer made clear the violation of the norm. The term ‘inhumanity’ is either a reference to the in-formal norm or else it is meaningless. The sanction was immediate: the maximum and officially prescribed offensiveness. The author, however, makes clear that such retaliation was not the rule.

The disapproval (and reply) of the British troops to this unusual transgression was an attempt to re-establish the ‘quiet front’, rather than deal death to the ‘enemy’ as the Generals wanted on a day to day basis. Interestingly this negative sanction also reciprocally applied to their own actions and those of their officers as was explained by another ‘Tommy’:

‘The most unpopular man in the trenches is undoubtedly the trench mortar officer, he discharges the mortar over the parapet into the German trenches . . . for obvious reasons it is not advisable to fire a trench mortar too often, at any rate from the same place. But the whole weight of public opinion in our trench is directed against it being fired from anywhere at all’

In this case the decisions of the trench mortar officer could seriously damage the unwritten ‘agreement’ by unleashing the negative sanction, this time from the German-side, and in so doing endanger British lives.

Such tacit ‘agreements’ as ‘live and let live’ combined with the ritualization and routinization of offensive activity had to remain partially or wholly ‘hidden’ from the upper echelons of military command on both sides, else the ‘agreements’ would be forcibly broken by these powers. It had to ‘look’ and ‘sound’ like something was happening for the benefit of the ‘brass’, even if the troops themselves were in little danger. Ashworth notes:

We have here a curious and paradoxical situation in which a ritualized and routinized structure of offensive activity functioned within the informal structure as a means of indirect communication between antagonists. The intention to Live and Let Live was often communicated by subtle yet meaningful manipulation of the intensity and rhythm of offensiveness. The tacitly arranged schedule which evolved established a mutually acceptable level of activity. To the uninitiated observer such a front line would appear to show a degree of offensive activity compatible with officially prescribed levels; for the participants, however, such bombs and bullets were not indicators of animosity but rather its contrary.

So it was necessary that the collective ‘fraud’ was tacitly accepted by all (including front-line officers) and kept secret from the ‘brass’, as this was in the interests of both the British and German combatants.

Ashworth concludes his paper by noting that such forms of cooperation by supposed front-line adversaries began to undermine the nationalist propaganda which was intended to divide them from ‘the enemy’ and motivate them to kill each other. He argues:

The experience of tacit co-operation came as a reality shock to combatants. It demonstrated to each side that the other was not the implacably hostile and violent creature of the official image. The latter eroded and was replaced, as we have seen, by an indigenous definition based on common experience and situation. This deviant image stressed similarities rather than differences between combatants. The institutionally prescribed and dichotomous WE and THEY dissolved. The WE now included the enemy as the fellow sufferer. The THEY became the staff. read more

PHOTOGRAPH: Ville Varumo

All we are not stares back at what we are

December 4, 2013 § Leave a comment

Everyone who was born after 1980 grew up with easy access to pornographic videos. Many children see explicit videos at a young age. Clark interviews people between the ages of 19 and 23 and asks how seeing pornography at such a young age shaped how they think about sex. watch

PHOTOGRAPH: Rosa Rendl